Don’t Look Now, But There’s an Ancient Roman Depiction of a Dolphin Under Your Bed

a (slightly updated!) inquiry, with pictures and Benjamin Franklin

Hello readers! I’m on vacation this week, so I haven’t written anything new. But I have been thinking about members of the delphinoidea superfamily apropos of absolutely nothing — more next week on that — so I decided it’s time to revisit and update this eight-year-old piece from the Eidolon archives, one of my favorite things I’ve ever written. I’ve condensed it to fit Substack’s email length limitations (although it may still get a little cut off, sorry) and I’m ending with a brief note to my reply guys. Enjoy!

The ancient Romans conquered the Mediterranean. They gave the world legendary badasses both real and fictional, such as Julius Caesar, Spartacus, and Decimus Meridius Maximus (yes, that’s the correct order). And they were terrified of dolphins.

You can tell a lot about cultural fears from iconography, and to the Romans, dolphins didn’t look like this (an image telling its own creepy tale about the American obsession with cuteness, but that’s a story for a different time):

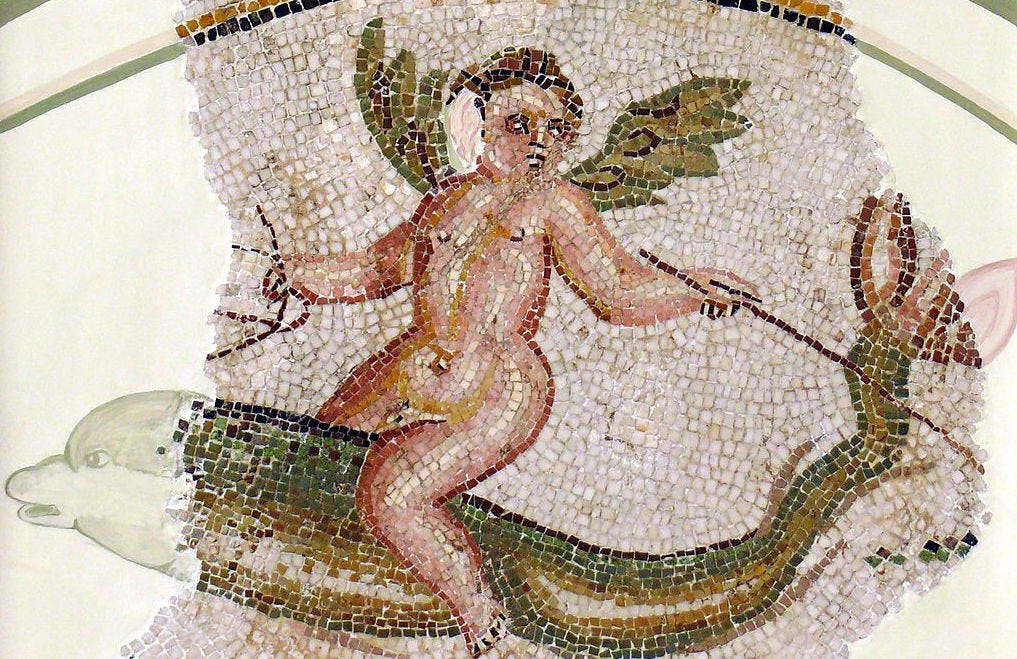

Instead, they looked like this:

Thank you, mosaic artist, for making sure the teeth were picked out in black tiles. Your effort is noted and appreciated (not really). Also noted: the demonic yellow eyes and crab-pincer tails, and their size relative to Eros (often depicted riding a dolphin). These are what nightmares are made of.

I became aware of the creepiness of ancient dolphins the first time I visited Rome, many years ago. Since then, this question has bothered me: how did the Roman perception of dolphins come to diverge so sharply from our own Flipper-and-Sea World version?

I’m not going to answer that question here. Instead, I’m going to show you some pictures of dolphins and share Benjamin Franklin’s insane theory for why paintings of them are so inaccurate and terrifying. In the end, you will be a little confused but probably not any wiser. I have warned you.

The ancient Greeks loved dolphins. They called them philomousoi, music lovers, because they thought that dolphins danced when they heard music. Taras, the mythological founder of the Greek city Tarentum on the south coast of Italy, rode there on a dolphin; the city adopted the image of a man riding a dolphin on their coinage. The Homeric Hymn to Dionysus recounts the story of how Dionysus was taken captive by a ship of pirates and turned them all into dolphins, and Herodotus tells a similar story about how the poet Arion was captured by pirates, jumped overboard, and was rescued by a dolphin and carried to shore.

Unlike the Roman depictions of dolphins, most ancient Greek pictures of dolphins a) aren’t horrifying and b) appear to have been painted by people with at least a slight awareness of what a dolphin actually looked like. Greek dolphins run the gamut from childishly drawn to friendly-looking to moderately dissatisfied, but they never look like they want to eat your soul.

Here’s a fresco from Knossos that, in spite of being more than 3,500 years old, might be able to pass as a page of Lisa Frank stickers:

Classical Greek dolphins, while hardly anatomically accurate, probably won’t frighten you and are actually kind of cute:

This is probably my favorite Greek dolphin:

Is he thrilled to be the steed of a naked satyr carrying a giant amphora? No. But he looks more or less resigned to his lot in life. He seems to be thinking, “I guess I’m a stool now. Oh well. At least I have eyelids.”

So far, so good. But just wait until we cross the Ionian sea.

Literary evidence from ancient Rome paints a similar picture of dolphins to the one we find in Greece. Pliny the Elder believed that dolphins loved music, and he tells several stories of close bonds of friendship between dolphins and humans. (He also says that they have spines on their backs and mouths in the middle of their stomachs, so he may not be a credible source.) His nephew, Pliny the Younger, in a move familiar to everyone who has ever tried to sound clever at a party, tells the exact same story about a dolphin that formed a close attachment with a boy in North Africa while pretending it was his story to begin with.

Mosaic evidence suggests that the Plinii may have been outliers in their warmth toward cetaceans. I’ll let you decide whether this mosaic dolphin carrying Cupid seems to be thinking “Let’s be best friends!” or “Once I get you far enough out to sea that nobody can hear you scream, you’re going to be my dinner”:

The next one is my favorite, and not only because of Cupid’s bizarrely svelte waist. It’s so obvious that whoever reconstructed the lost parts of the mosaic was really trying to make the dolphin seem nice:

Cute! But I think we can all agree that the museum went with a conservative estimate of how many dolphin teeth would have been visible, considering this statue, also of Cupid riding a dolphin, from the very same time period:

In conclusion, ancient Roman dolphins resemble nothing so much as Flotsam and Jetsam from The Little Mermaid, if they were actually scary eels and not incompetent henchmen.

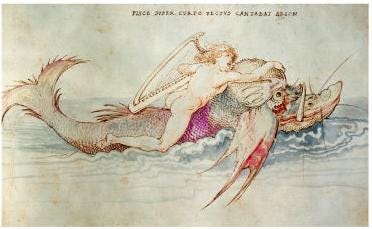

Later painters in western Europe — who I guess had never actually seen a dolphin with their own eyes? — more or less took the Roman depictions of dolphins as their models. Later European dolphins are even toothier and hairier (literally, not figuratively) than their predecessors.

Albrecht Dürer, an absolutely brilliant artist who specialized in woodcut prints, apparently thought that dolphins had tusks and whiskers. His Arion, naked but for his full-sized concert harp, looks like he’d prefer to take his chances with the pirates:

Here’s “The Triumph of Galatea” by Raphael, also from c. 1514, with a close-up on its dolphins:

BRB, never sleeping again.

The seventeenth century wasn’t much better for dolphin pictures. For the record, I’m not in favor of the adorable little bow-carrying cherubs we use to represent Cupid/Eros. In the ancient world, a bow was a serious weapon. If we want to translate that image, we should depict Cupid as a toddler holding a handgun (something that happens in the U.S. with a frequency more terrifying even than the dolphin images in this article). Regardless, it’s impossible to take this Cupid with his dinky little bow seriously, seeing as he’s riding on what appears to be a feral hog with scales and fins:

By this point, you’re probably wondering two things: how did European art get sent down this path of inaccurate and scary dolphins, and why do I care so much? I’m going to flat-out ignore that second question, because I found an interesting answer to the first from none other than Benjamin Franklin.

In a diary he wrote during a sea voyage in 1726, 20-year-old Franklin shares some thoughts about dolphins:

This morning the wind changed; a little fair. We caught a couple of dolphins, and fried them for dinner. They eat indifferent well.

I’m using that expression every time I eat something mediocre from now on.

These fish make a glorious appearance in the water; their bodies are of a bright green, mixed with a silver colour, and their tails of a shining golden yellow; but all this vanishes presently after they are taken out of their element, and they change all over to a light gray. I observed that cutting off pieces of a just-caught, living dolphin for baits, those pieces did not lose their lustre and fine colours when the dolphin died, but retained them perfectly.

WHY WOULD YOU DO THAT, CREEP? Oh, right, “science.” Go back to electrocuting yourself with a kite and a key and leave the dolphins alone.

Every one takes notice of that vulgar error of the painters, who always represent this fish monstrously crooked and deformed, when it is, in reality, as beautiful and well-shaped a fish as any that swims. I cannot think what could be the original of this chimera of theirs… a crooked monster, with a head and eyes like a bull, a hog’s snout, and a tail like a blown tulip.

Ok, that’s a pretty good description.

But the sailors give me another reason though a whimsical one, viz. that as this most beautiful fish is only to be caught at sea, and that very far to the Southward, they say the painters wilfully deform it in their representations, lest pregnant women should long for what it is impossible to procure for them.

Wait, what?

I don’t like to play the “I’ve been pregnant and so I know what I’m talking about” card, but I’ve been pregnant and I know with 100% certainty that pregnancy cravings, while occasionally unpredictable, have absolutely nothing to do with the cuteness of the food craved. Not once in either of my pregnancies did I think “You know, that puppy is adorable, I guess I should EAT IT.” Usually I was just like, “My iron might be low because that spinach looks really damn good.” Then again, I’m the person who researched and wrote this article, so I’m not exactly normal.

While writing this piece and talking to everyone I came across about scary ancient dolphins, several people pointed out that there’s good reason to depict them as frightening: dolphins are not always cute and are often kind of terrifying. This Slate article points out that dolphins like to headbutt their own children for fun, gang-rape female dolphins, and can go for a week without sleeping. The article ends on this very valid point: “After all, you never hear about the people the dolphins push out to sea.”

I like to think that someone in the early history of Rome suffered a Jaws-style dolphin attack and the horror became etched into their cultural consciousness, but that’s just a guess. I don’t really know how they became such terrifying monsters in the Roman cultural imagination.

Cheryl Strayed once wrote that “the invisible, unwritten last line of every essay should be and nothing was ever the same again.” That’s a little ambitious for an article that’s little more than a string of increasingly horrifying pictures, but you’ll probably never look at Lisa Frank’s happy technicolor dolphins the same way again.

I’ve been emailed about this piece more than anything else I’ve ever written, including the ones I got hate-mail for. Every few months, some man (always, always a man) really needs me to know that Benjamin Franklin was talking about “dolphinfish”, aka mahi mahi. They’re probably right, but: A) if you look at the comment section, you’ll see that five people have made this point already; B) my joke stands regardless; and C) mahi mahi don’t eat “indifferent well,” they’re delicious. That is all.

Absolutely understand why this piece is found to be so interesting. I think the Romans were just fixated on their version of horror flicks. It was just in the blood for most of the popular entertainment! As for Ben, I think there is probably a hidden psychopath narrative there. He was definitely into self harm! This piece is so funny, you made me snort laugh a couple of times! Happy vacation Friday!