Hades 2 is allegedly going to be released in early access this Spring, and I could not be more excited. Hades is one of my all-time favorite games. It contains so many of my favorite things in one beautifully designed package: it’s an exciting roguelite with fun synergies AND a moving story with memorable characters and dialogue, and best of all, the game mechanics and story beats are woven together in a way that feels deeply satisfying. And on top of all that, it’s a genuinely fresh and original take on familiar stories from Greek myth! Of course I love it. If you want to hear me gush about the game for over an hour, I once did so on the Movies We Dig podcast.

Unfortunately, there’s one thing about the game that really, really bothers me. The writers definitely captured the inherent messiness of the family dynamics in the Greek pantheon… but along the way, they sacrificed one of the most singular and meaningful relationships for the sake of narrative.

Yes, I’m coming back yet again to one of my very favorite topics: the fraught nexus of Greek myth, pop culture, and parenting. But before I explain further, I’m going to need to give some spoilers.

In Hades you play as Zagreus, the bratty son of Hades, god of the underworld. The game begins at exactly the moment when Zagreus has just exclaimed, “You can’t tell me what to do, DAD,” and decided he’s going to run away from home. He has to fight his way through his father’s minions using only a basic attack, a special attack, a cast, and a dash.

Fortunately, the Olympian gods are psyched to meet their newly discovered nephew/cousin/both (incest aplenty can make those divisions sort of hazy), so they offer Zagreus their help, empowering his basic moves with their unique flair. Zeus’s boon adds a chain-lightning effect to your attack, while Dionysus can give enemies stacks of a “hangover” effect that does damage over time (been there). That sort of thing.

You fight through different, procedurally generated levels of the underworld, each with a boss at the end, until you either reach the surface or – more likely, at least at first – die. When you run out of hit points, Zagreus is teleported back to the House of Hades, where he can talk to his Underworld friends and relatives and they can comment on his life choices. When you’ve spoken to everyone, it’s time to go back out there and try to break free again, and the cycle continues with a fresh run.

You quickly learn that Zagreus has reasons to break free aside from hating the boring desk job his dad wants him to take more seriously. As it turns out, shortly before the events of the game, he discovered he’d been lied to his entire life about his parentage. He thought his mother was Nyx, goddess of night, mother of many chthonic gods and a strong maternal presence in the House of Hades. But his real mother is Persephone, daughter of Demeter, goddess of the harvest. He’s determined to find his birth mother and meet her for the first time – and, hopefully, understand why she left him in the first place.

After hours of gameplay and many ignominious deaths to those annoying shield enemies in Elysium and Theseus (an unbearable blowhard), the story gradually unfolds, and Zagreus and the player find out why his family is such a mess (although, in the scheme of dysfunctional Olympian families, it could be a lot worse). The backstory is that when Zeus, Poseidon, and Hades drew lots for what their kingdoms would be and Hades picked the underworld, Zeus felt a little guilty. He saw an opportunity to kill two birds with one stone: Persephone was unhappy on Olympus under the thumb of her controlling shrew of a mother, and Hades had clearly gotten the short straw in the kingdom division, so why not spirit Persephone away and offer her as a consolation prize?

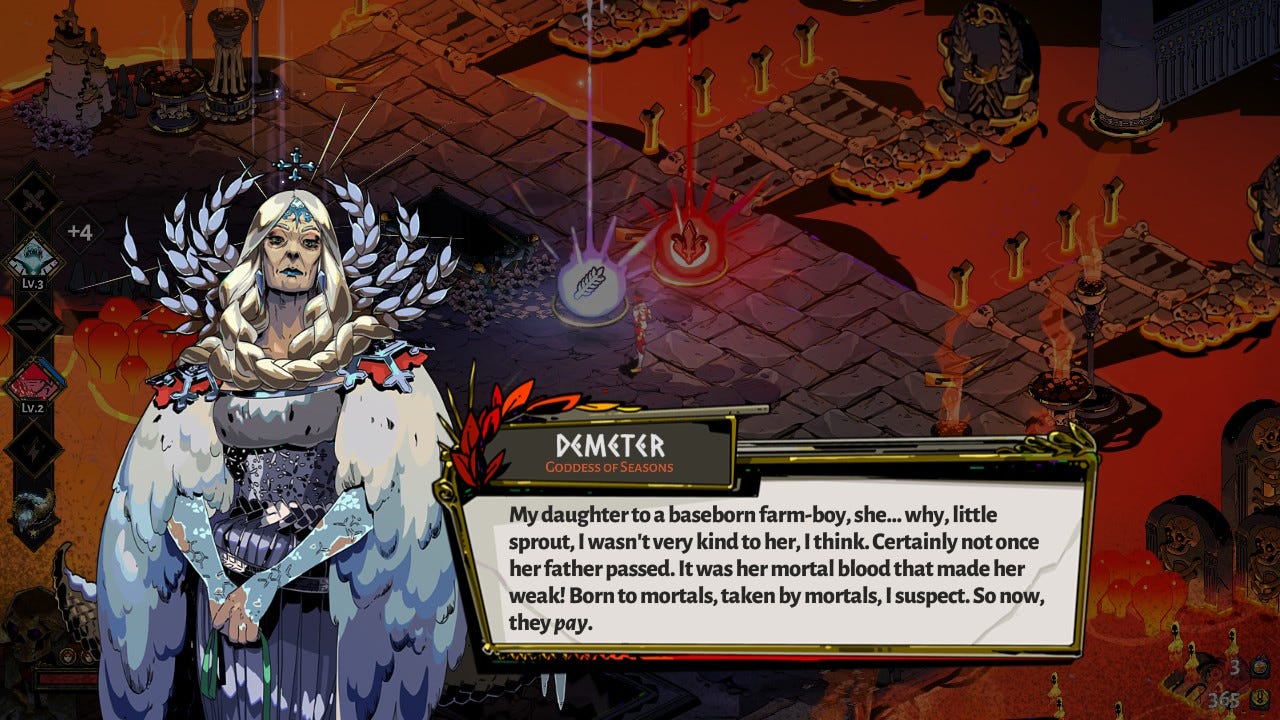

Although both Hades and Persephone thought Zeus’s abduction plan sucked, they liked each other, so they stayed together and had Zagreus. But he died soon after birth, and Persephone left the underworld and went into hiding. Nyx was able to resuscitate Zagreus, but she and Hades decided that for everyone’s safety, Persephone should stay hidden. You see, when the game begins, Demeter still has no idea where her daughter disappeared to, and to say that she’s not thrilled would be an understatement. She’s blanketed the human world in eternal winter as a punishment and has sweet ice abilities to offer you as weapon upgrades.

So far, so Homeric Hymn to Demeter. Eventually, Zagreus is able to convince Persephone to return to the House of Hades with him, and their family is reunited. His father hires him as a security expert so he can keep finding weaknesses in the underworld’s defenses through his breakout attempts, which is such a fun and clever way to allow the player to keep playing the game even after the main narrative arc wraps up. If you play further – like, to around 50 victories – you can even set up a giant dinner party where Zagreus and Persephone are reunited with their Olympian relatives, awkwardly forgive each other, and vow to never discuss it again and move on.

There’s so much to love about this reimagining of the Hades/Persephone myth. For one thing, Hades isn’t a rapist, which might feel like a super low bar but is actually pretty impressive for Greek myth! That leaves the player free to root for that cozy family reunion without feeling gross. The game designers also got the vibe of the Olympians exactly right. One of my favorite game mechanics is the “Trial of the Gods,” a challenge that gives you a choice between two different blessings. Whichever god you don’t choose immediately gets offended and tries to murder you for a little while before giving up and getting over it. That pettiness and changeability? Note-perfect.

The game is also filled with delightful bonuses for classics nerds. There’s Zagreus himself, whose identity as the son of Hades and Persephone is attested in a single fragment from Aeschylus’s lost Sisyphus. (Incidentally, Sisyphus is also a minor character, and he’s completely cheerful about his lot – exactly as Camus imagined him.) Black Athena. There are character-driven side quests to unite Achilles and Patroclus in the underworld and to get Eurydice her fair share of the credit for Orpheus’s hit songs. Cerberus is a very good boy and you can pet one of his heads as much as you want. The pantheon is depicted as racially diverse and queer as hell.

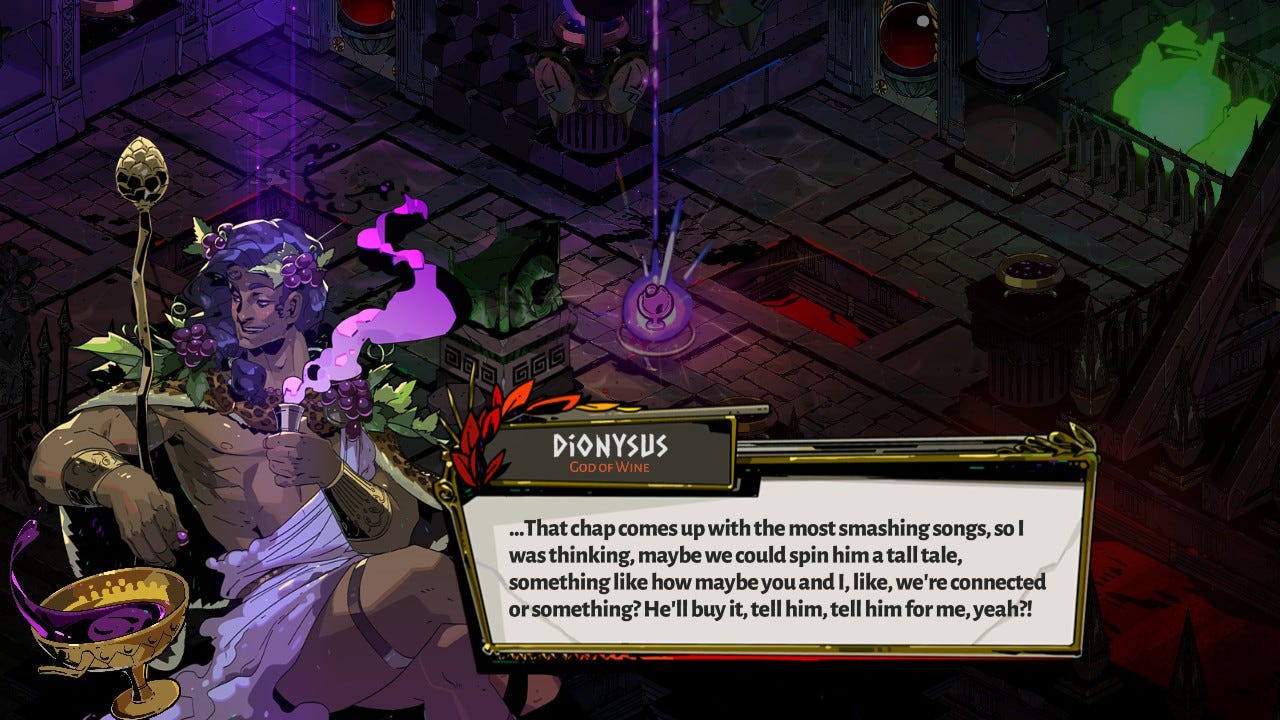

The most bonkers niche classics Easter egg in the entire game is a brief interaction between Zagreus, Dionysus, and Orpheus. Dionysus suggests that Zagreus play a hilarious prank on Orpheus:

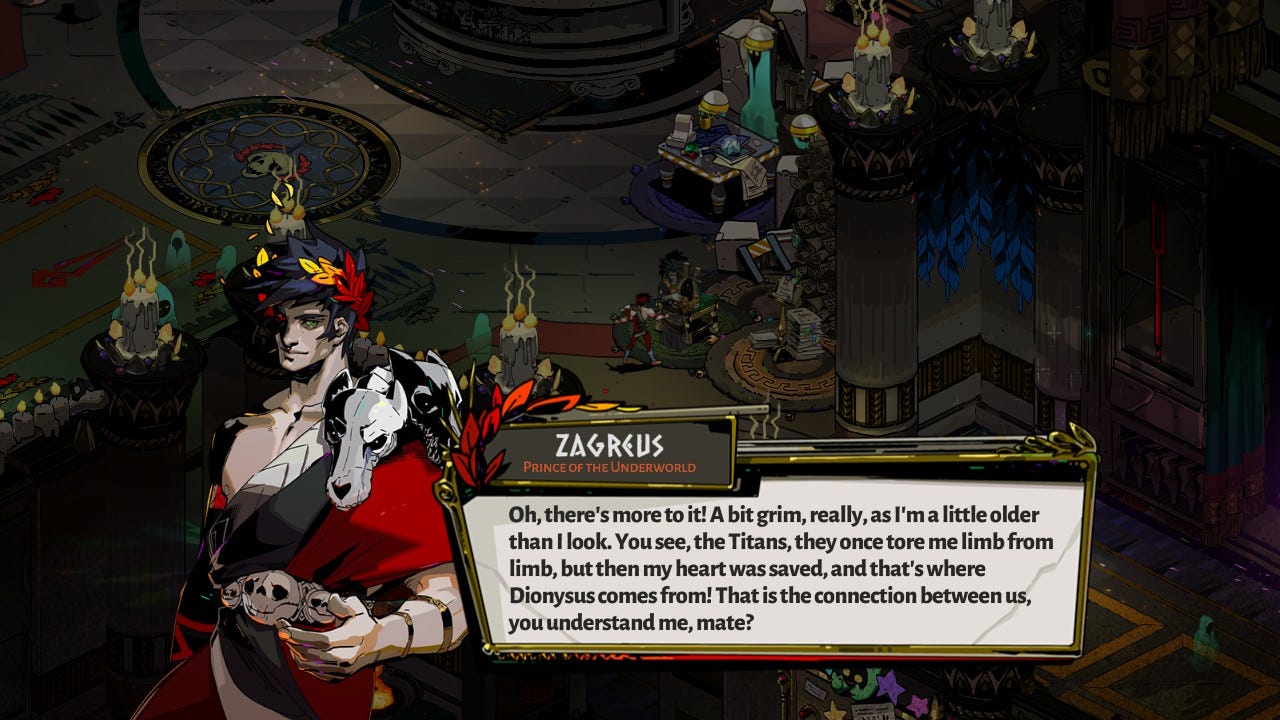

The next time you return to the House of Hades, Zagreus tells Orpheus, even elaborating one step further:

Orpheus will then write a song celebrating “Dionysus Zagreus.” This is some of the nerdiest shit I’ve ever seen. It’s a reference to the Orphic hymns, associated with a mystery cult in which, you guessed it, Dionysus Zagreus was torn apart by the Titans and then reborn. This is stuff so niche that even many mythology fans don’t know about it. Most Greek religion followed an “opt out at your own risk” model where the safest bet was to honor all the gods and not risk upsetting any of them. But mystery cults were opt-in, a chance to learn secret stories and have a chance at a better afterlife.

The most famous mystery cult was the Eleusinian mysteries, associated with Demeter and Persephone. This mother/daughter pair is also at the heart of my biggest complaint with Hades. Almost uniformly in Greek myth, Demeter and Persephone are depicted as a very tightly knit duo. Almost inseparable, except that, of course, for part of the year they must be separated, and when they are the entire earth mourns.

There are so few close, loving mother/daughter relationships in Greek myth. Did Supergiant really have to eviscerate this one?!

The Persephone of Hades makes it very clear how much she hated living on Olympus with Demeter. She especially hated Demeter’s name for her, Kore… the name often used for Persephone in the context of the Thesmophoria, a major annual festival for women celebrating the two goddesses. A huge celebration of feminine energy with no men allowed. Sounds great… unless, you know, you retell the story so Persephone hates her mom.

I understand why this choice was necessary from a narrative perspective – if your story is that Persephone came to the Hades of her own free will (sort of), she had to have a good reason for doing so. But come on. Why does the most remarkable example of the power of a mother/daughter bond have to be the collateral damage?

This isn’t a critique of the game per se. It just makes me sad. It feels like an extension of the dead Disney mom trope.

And it isn’t even the game’s only crime against motherhood! Let’s not forget how Nyx, Zagreus’s adoptive mother, gets shunted to the side as soon as he learns about Persephone. Eventually, when you’re a few dozen hours into the game, Zagreus acknowledges the labor she put into raising him, but it takes a while.

Why aren’t there more depictions of mother/daughter relationships that are challenging but also close and loving? I’m not saying their relationship should have been easy or simple. Literally no woman I know has a simple relationship with her mom. But many of us are close to our moms and adore them! There has to be room for stories that don’t fall into the tired tropes of “you’re just like your mother” accusations or Black Swan-type codependent toxicity. Where two women really love each other and have a sometimes-eerie amount in common but are different enough that their relationship can be challenging in a generative way. Is that so much to ask?!

Supergiant has announced that Hades 2 revolves around Zagreus’s half-sister Melinoe. Presumably their shared parent is Hades, so there’s a chance that this game will take maternal labor seriously. Maybe Melinoe’s mother has been a consistent, formative, securely attached presence in her life! We’ll know in a few months.

And even if not, I’m sure the game will be terrific and will suck up many hours of my time, because let’s be real: “Hades, but make it witchier” was always going to be a slam dunk for me.

As a final, closing thought, I want to make a plea to my readers to take video game classical reception seriously. I know I write about a lot of not-so-serious topics in this newsletter, like puff pastry stuffies and TV shows for kids and grammar pedantry. But video games are pretty serious for me, actually.

Over the holidays, my brother and I were talking about video games we’ve been playing, and my dad said, “You know, there was a time when I might have gotten really into playing video games, but instead I decided to be a serious person.” Ouch, Dad! Unfortunately, I think this type of attitude is pretty common, and many people who value classics might under-value video games as a topic of serious inquiry. And they shouldn’t.

Video games have changed a lot since the days when my father absolutely crushed at that one Atari bouncing clown game. In a beautiful essay about Disco Elysium (which I wrote about a bit here a few weeks ago), Nana Kwame Adjei-Brenyah calls the game “a magnificent literary experience.” He continues, “Literary is a slippery and sometimes problematic word, but in this context I mean: via the precise use of language, it changes the reader.”

Hades is also, I would argue, a literary experience. It contains some 20K lines of written dialogue. In addition to being literary, it’s also significant: it’s sold well over a million copies. It is every bit as important a piece of contemporary classical reception as the Broadway play Hadestown (which covers some similar mythological ground) or Madeline Miller’s Circe. In fact, Miller is working on a new book about Persephone, which I can’t wait to read – but I bet I’ll spend less time with it than I did with this game, and it will give me less joy (and, judging from her other books, is more likely to use sexual assault as a narrative element for character development and plot momentum).

I’m definitely not saying that all video game writing is good. In fact, much of it is pretty bad. Many game designers undervalue writing as a component of the player’s experience of the game and think of it as a priority far behind mechanics and visuals. But great game writing does exist, and games like Hades deserve to be taken seriously as not just a fun diversion but as literature and significant sites of classical reception.

And that’s plenty of soapbox for now. I’m going to go and try to beat my highest heat level with the gloves. And pet Cerberus. He’s a good boy.

There’s a webcomic I really like called Lore Olympus that pulls a similar move - Hades not a rapist but Demeter an overprotective mom. I’m hoping that there’s an arc where stuff gets better between Persephone and Demeter.