You may have noticed that, for someone who writes a newsletter called Myth Takes, I don’t spend a lot of time retelling specific tales from myth. My goal here isn’t to cover ground similar to the “introduction to myth” courses I’ve taught; I’m trying to explore what myth (and classics more generally) means in my life and in the contemporary world while connecting with a delightful community of like-minded readers who are as overwhelmed as I am by the current surge of Circe-esque novels. I might spend some time reflecting on how distressing it is that each of Jupiter’s major moons is named after one of his victims of sexual assault, but I’m probably not going to recount all of those stories in detail.

Fortunately, if you’re looking to broaden your knowledge of Greek myth, there are a ton of fantastic resources out there. They come in many formats, including an excellent podcast. But I’m an old-fashioned nerd at heart, and I still prefer to get my information from books.

These are my favorite books about myth, the ones I recommend over and over. I hope you enjoy them as much as I do.

Seriously Great Sourcebooks & Scholarship for Serious Myth Nerds:

Anthology of Classical Myth: Primary Sources in Translation (edd. Trzaskoma, Smith, and Brunet)

I honestly don’t know how people taught myth classes before this book existed. (A lot of photocopying, I imagine.) It’s AMAZING. 400 pages of excerpts from a diverse array of authors, including the big names (Euripides, Sappho, etc) but also snippets from authors that your average reader is less likely to know, like Hellanicus, Parthenius, and Xenophanes. It also includes long excerpts from Apollodorus and Hyginus, the two most important mythographers you’ve never heard of if you’re not a classicist (and there’s a supplementary volume with more of them for real ones). An absolutely indispensable resource.

Because I’m a pain in the ass, I do have one tiny note on it, which is that it’s organized alphabetically by author. Which makes sense, I guess — you need to choose SOME kind of organizing principle — but I’d have much preferred a broadly chronological organization, which might give readers a sense of how different authors allude to and build on each other. I do get how dating can be really challenging sometimes and how the alphabetical organization is probably easier for most readers, but guess what? This is my newsletter and I get to talk about my minor preferences as much as I want. Ha. But please take this entire digression as being more about me than about the book, which is wonderful.

Classical Mythology: A Very Short Introduction (Helen Morales)

Don’t knock the Very Short Introduction series, which contains some really excellent books. (Also, if you haven’t read this excellent New Yorker piece about the series, it’s a treat.) Helen Morales is a brilliant scholar I adore, and this book rocks. For such a tiny volume, it’s incredibly far-ranging in its approach to how myth has been used in politics, culture, and art in the past hundred years, all while staying very firmly grounded in the original sources and contexts.

Just to give you a sense of how smart this book is, please enjoy these screenshots:

Any book that can both include this table AND deconstruct/critique it is just *chef’s kiss*.

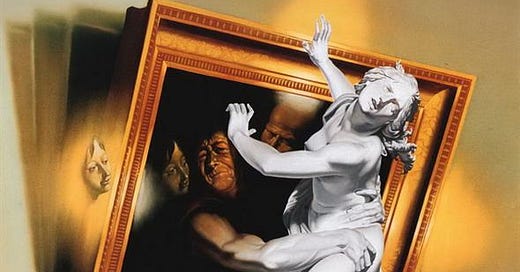

The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony (Roberto Calasso)

It is not an exaggeration to say that this book made me a myth scholar. It’s one of my favorite books of all time. That said, it’s been somewhat divisive among my myth students over the years because its form is so experimental and literary and dense and lovely. If you’re looking for a chill, chatty retelling of myth, there are tons of great ones — Stephen Fry is a favorite of many, and there are classics like Hamilton and Graves and honestly too many others to count.

But Calasso is in a class of his own. This book doesn’t just retell the myths gorgeously, or analyze the ancient texts in which we find the myths, although it does do both those things. What makes it so remarkable is that it itself reflects on the importance and impossibility of the task of encapsulating what myth is in literary form. Here Calasso writes about the task of mythography (pp. 280-1):

Myths are made up of actions that include their opposites within themselves. The hero kills the monster, but even as he does so we perceive that the opposite is also true: the monster kills the hero. The hero carries off the princess, yet even as he does we perceive that the opposite is also true: the hero deserts the princess. How can we be sure? The variants tell us. They keep the mythical blood in circulation…

The mythographer lives in a permanent state of chronological vertigo, which he pretends to want to resolve. But while on the one table he puts generations and dynasties in order, like some old butler who knows the family history better than his masters, you can be sure that on another table the muddle is getting worse and the threads ever more entangled. No mythographer has ever managed to put his material together in a consistent sequence, yet all set out to impose order. In this, they have been faithful to the myth.

The mythical gesture is a wave which, as it breaks, assumes a shape, the way dice form a number when we toss them. But, as the wave withdraws, the unvanquished complications swell in the undertow, and likewise the muddle and the disorder from which the next mythical gesture will be formed. So myth allows of no system. Indeed, when it first came into being, system itself was no more than a flap on a god’s cloak, a minor bequest of Apollo.

It’s especially cool to read Calasso alongside Morales because both start with Europa, but in ways that are about as different as they could conceivably be. Calasso tells and retells the story, digging deeper into the refractory nature of myth using Io and Zeus and Europa and bulls and Ariadne, picking out the recurring motifs from every angle. Morales looks at the image of Europa on the Greek 2 Euro coin and how Europa has been used by Greece as a symbol to establish a claim over and place in European identity. Both address the sexual assault aspect, which I appreciate. Fry’s Europa is completely 100% into it, which is… a choice.

Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources (Timothy Gantz)

I’ll be honest: there’s almost no chance that you need this book. But I have to include it because it’s the resource I turn to more than any other. Say you’re, I don’t know, writing a newsletter about Sisyphus, and you want to know which ancient sources he shows up in. This is the book you turn to. It includes both literary and artistic sources, which is an especially useful touch, because a lot of what we know about myths comes from pottery.

You’d have to be in the top few percentiles of myth obsessives to have a use for this book, but I don’t know where I’d be without it. Completely indispensable to some of us, while the rest reap the fruits of its systematic organization unknowingly.

For Those Who Come Here for Feminist Cultural Critique:

Antigone Rising (Helen Morales)

More Morales! What can I say? I love this book so much. Broadly speaking, it’s about the meaning of myth in contemporary culture, but that doesn’t really get at how fun it is. Morales looks at Beyonce and queer YA novels and diet culture as sites of classical reception with the regard and thoughtfulness most scholars only reserve for Serious Male Literature and the like.

This book is sometimes very funny, and sometimes gutting, as when she writes about #MeToo and sexual assault in myth (p. 72):

Predatory men still silence women; the removal of Philomela’s tongue was the original nondisclosure agreement. At its core, the myth of Procne and Philomela is a myth about the refusal of a rape survivor to be silenced and the ability of women to take down abusive and powerful men, when they work together to do so. Procne could have chosen to side with her husband and to keep her son and all the social advantages of being queen. Instead, she chose to support her sister, at great cost to herself. She chose rage.

In fact, I’m going to go out on a limb and say that if you like this newsletter, there’s an excellent chance you’ll love this book. I suspect our Venn diagrams of ideal readers is pretty much a circle. This isn’t an accident — she was on the editorial board of Eidolon, and we wrote an article together about Antigone and Greta Thunberg, so we share a lot of similar interests. We even cover some of the same material — if you liked my Lysistrata podcast and newsletter, you’ll for sure enjoy Morales’ chapter about Lysistrata, Chi-raq, and Leymah Gbowee.

Pandora’s Jar (Natalie Haynes)

Natalie Haynes is another of my favorite writers on myth, and her other books about myth are also great (and her fiction!). This one is my current favorite, maybe just because I’m working with a lot of Odyssey material for my memoir and she’s so great on Penelope (p. 283):

And this is the great difficulty in finding Penelope among the praise heaped upon her by men. Are they describing her, or merely describing their idealized conception of what a wife should be? Which seems to be one who is competent, self-sufficient and conveniently far away. One who either doesn’t know, or at least doesn’t complain, that her husband has adventures (sexual and otherwise) with seemingly little recollection that he has a wife at all. And one who doesn’t do the same herself. Are they valuing her for nothing more than her chastity? Or, more specifically, for her chastity in the face of so many men apparently desiring her?

The chapters of this book each focus on a woman (or group of women, like the Amazons, or monster, like Medusa) from myth. So it might be a little more accessible to some than Antigone Rising, where the chapters are organized thematically by cultural issue. The latter is a little more my jam than the former, but that’s entirely a question of personal taste.

Women and Other Monsters: Building a New Mythology (Jess Zimmerman)

Speaking of things that are exactly my jam: this book braids together female monsters from myth with reflections on how hard it is to exist as a woman in the world, and there’s nothing I like more than that. Teenage angst about ugliness and beauty read alongside the power of Medusa’s gaze and the resonance of using “Medusa” as a username? Yes, please, I would like an IV of that directly into my veins (p. 12):

This is being a teenage girl in microcosm: I had bad skin, didn’t know how to wear makeup, and was too fat to look good in a prom dress, not that I tried, so I must be so ugly that to merely look upon me meant certain death. It’s a dramatic time of life. And truth be told, even then I knew going by “Medusa” was audacious. It was a jaded shrug, an attempt to recuse myself from the game of human attraction before anyone pointed out that I’d already lost. What better defense against being considered insufficiently beautiful than to stake a claim on definitive, unassailable, remarkable ugliness? But every time I logged in, I felt a little intimidated by my own swagger. Medusa and the other Gorgons were hideous in a way that went far beyond not being pretty. What was I thinking, aligning myself with Medusa—not an ugly woman but the ugly woman, the avatar of ugly power? Medusa doesn’t just fail to measure up; she turns ugliness into a weapon. She’s so ugly it hurts—but it doesn’t hurt her first.

We’re definitely in the realm of memoir here — Morales is a classicist, and Haynes is a writer who has studied and written about classics extensively, but Zimmerman is less rooted in the ancient source material. Which isn’t a knock on this book at all. Don’t come to it because it will teach you the most you can learn about Medusa. That isn’t Zimmerman’s goal, and there are better sources for that (some of which I’ve already mentioned and linked to). Ignore the Amazon reviews that complain that this isn’t a scholarly book about monsters in myth and feminist scholarship — there’s nothing worse than a review that says “I thought this would be about X, but it’s about Y, and honestly it did a bad job of X, a thing it was never trying to do.” (This is, unfortunately, a significant percentage of all book reviews. Which sucks.)

One eensy, microscopic, infinitesimal note — on p. 51, in her otherwise excellent chapter about Scylla, she writes, “To Homer, writing in the eighth century BCE, Scylla was a twelve-legged, six-headed, barking creature with no human characteristics to speak of.” And I have to admit, that was a hard moment for me. It’s one (completely fine!) thing to write a book like this without being a classicist, and another to seem unaware of the broad scholarly consensus that there was no “Homer” and that the Homeric epics were produced through an oral tradition and not written down until much, much later. I do think that as an author you’re making a claim to, well, authority, and that kind of error was jarring enough to me as a reader that I had to take a step back. But after some shower self-reflection, I realized I didn’t care, it didn’t really impact the book at all, and being pedantic helps nobody really and can deprive the pedant of a lot of opportunities to learn. But I did want to issue a bit of a warning that the level of classical knowledge here isn’t the same as you’d find in Morales and Haynes.

If You’re Trying to Nurture a Blossoming Myth Obsessive:

D’Aulaires’ Book of Greek Myths

The O.G. Still rules.

Goddess Power: 10 Empowering Tales of Legendary Women (Yung In Chae)

Yes, three of the ten books on this list are by friends of mine, but in my defense my friends are just really cool and smart. Yung In was an editor for Eidolon and is one of my favorite writers, and I can’t say anything else about her here or she’ll give me shit about it until the end of time. I will say, though, that every parent I know who has read this to their myth-obsessed daughter said that it was a phenomenal experience. So if you’re looking at a little girl in your life and thinking “man, it’s a bummer that she’s too young to read Circe”: start her here.

Echo Echo: Reverso Poems About Greek Myths (Marilyn Singer)

Maybe your little myth fan is too young even for Goddess Power, but you want to set her on the path toward myth obsession. This book is adorable. First of all, I love reading poetry with kids — Shel Silverstein 4eva — and this book has a really clever premise: all of the poems are told forward, and then backward, which shifts the meaning in really interesting ways.

In a way, it’s sort of the extremely starter version of Calasso’s “Myths are made up of actions that include their opposites within themselves,” right? There’s a clear through-line there, even if the level of difficulty is… somewhat different.

There are so many great books about myth out there — this post could easily be twice as long as it is. If I didn’t mention yours, feel free to share it in the comments! I would love to add more books to my already-terrifying TBR. As the wave withdraws (after reading a book), the unvanquished complications (of all the books you still want to read) swell in the undertow. But that’s the fun of it all.

One of the only Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony mentions I've ever seen! Truly a fantastic story, the parts I could understand blew my mind.

I've ordered the last two from your links just now! Excited to read them with/to my granddaughters.