Euripides’ Trojan Women is one of my favorite plays, but man, is it a downer. First performed in 415 BCE, the play follows the plight of the women of Troy after the war has ended and all the men of Troy are dead. Each woman’s fate is more horrifying than the last. The Greek general Agamemnon is taking the Trojan princess Cassandra away as his sex slave, but because she can see the future she tells everyone that Agamemnon’s wife Clytemnestra will soon brutally murder them both. Her sister Polyxena has already been ritually sacrificed at the grave of Achilles, the man who killed her brother Hector and desecrated his corpse.

As the play continues, we learn that Andromache, Hector’s wife, will be the slave of Achilles’ son Neoptolemus — and, even more horrifyingly, their son Astyanax will be executed because the Greeks think he represents too much of a threat of future Trojan reprisal. The play is anchored by the old Trojan queen Hecuba, who by the end has completely dissolved into grief.

In short, Trojan Women isn’t a play you’d go to if you’re looking for a pick-me-up (or even a satisfying-if-depressing narrative arc a la Oedipus, because the play doesn’t have a plot per se, just a series of consecutive disasters and laments). Still, it’s one of my favorites. I wrote about Trojan Women for Eidolon a while back, because it’s one of the most powerful and resonant tragedies I know. I wouldn’t be surprised if someone is adapting it with a chorus of Palestinian women at this very moment — it’s been staged dozens of times to speak to the devastating human costs of war and imperialist violence.

And also, it contains one of the dumbest fat jokes I’ve ever read.

Wait, what? This ancient Greek tragedy about the atrocities inflicted on women and children in war contains a fat joke? That seems a little… tonally inappropriate, doesn’t it? Why, yes. Yes, it does.

I’ll give you some context, even though I guarantee it will not really help. The fat joke appears in the final major episode of the play. Hecuba has already gotten more than 800 lines of devastating news when Menelaus — one of the generals of the Greek army and architects of Troy’s destruction — appears. Although they are enemies, he and Hecuba actually want the same thing: for him to execute Helen, Menelaus’ wayward wife and one of the causes of the entire conflict. But Menelaus wants to be the one to wield the sword, while Hecuba fears (correctly) that, given the opportunity, Helen will seduce Menelaus and escape execution.

Helen then appears and demands a chance to defend herself. She and Hecuba launch into one of Greek tragedy’s famous “structured debate” agon scenes that I discussed briefly in this newsletter. Hecuba “wins,” more or less — as Rebecca from Crazy Ex-Girlfriend says, “The situation’s a lot more nuanced than that!”, but as one of my favorite sociology papers says, “fuck nuance,” sooooo.

Unfortunately, Helen has succeeded in shifting the Overton window of the debate so the terms are “should Helen die or not,” so all that Hecuba’s victory means is that Menelaus still plans to kill Helen. Nothing has actually changed since the beginning of the debate. He still has no intention of taking Hecuba’s advice that he delegate Helen’s execution to someone a little less susceptible to her charms.

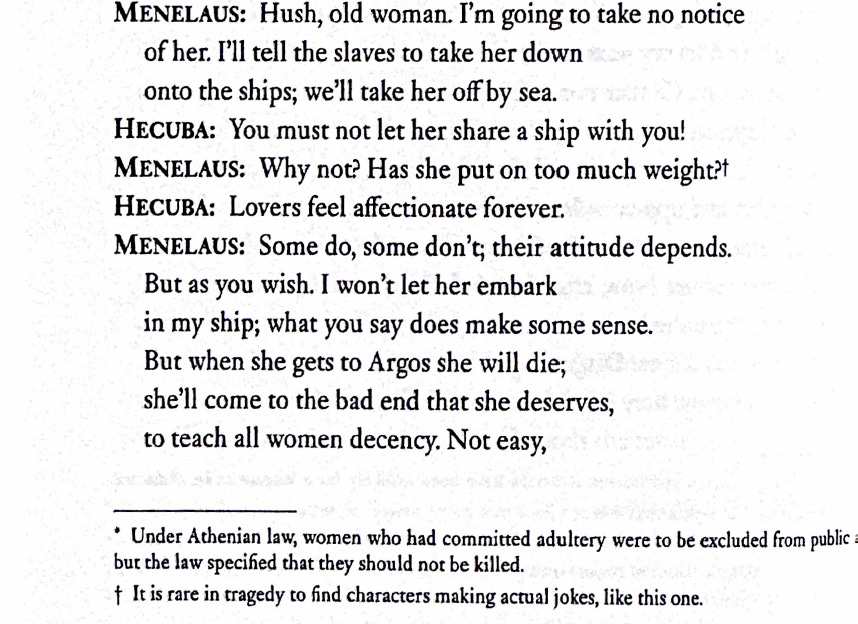

When he announces his plan to sail back to Greece with Helen, Hecuba asks that he at the very least not share a ship with her. His response is… well. I’m going to share Emily Wilson’s translation, since she’s my go-to translator whenever possible:

Incidentally, every so often, one of those “romantic quotes from Greece and Rome” lists/books will include Hecuba’s response to Menelaus’s fat joke, like this Shutterfly list. So if you ever see a list of romantic quotes that includes some version of “Euripides: ‘Lovers feel affectionate forever’”… now you know its unrelentingly depressing context.

Going back to the joke itself, though, here’s the Greek, for those interested:

Μενέλαος

τί δ᾽ ἔστι; μεῖζον βρῖθος ἢ πάροιθ᾽ ἔχει;

Literally, he says something more like “does she weigh more than she used to” — Wilson’s “has she put on too much weight” does give the sense of weight gained over time. Crucially, Wilson doesn’t even try to make this joke seem funny, although she does footnote it to give the reader some context: yes, you’re not insane, that is indeed a fat joke in Greek tragedy. Wilson explains more in her introduction to the play:

As Wilson argues, the mythic context here is crucial. There’s a lot of flexibility for variation in myth, but there are also some fixed points, and one of them seems to be that Menelaus and Helen will end up back together and live happily ever after. The details are less settled, sometimes only an eidolon of Helen went to Troy in the first place and she needs to be rescued from Egypt and sometimes she marries Achilles in the underworld after she dies and he’s her OTP, but whatever, none of that is important. What’s important is that we know that Menelaus’ resolve to kill Helen isn’t going to last, and that he’s every bit as weak as this joke is… if it even is a joke, which some scholars have questioned.

I’m not going to really go into this scholarly controversy, because YAWN. I promise you, nothing could be less interesting/amusing than me recapping a bunch of academics debating whether a bad 2500-year-old fat joke was indeed intended to be a fat joke. Suffice it to say, every so often a scholar comes up with a wild alternate theory. David Kovacs, an eminent Euripidean scholar, published a note in 1998 arguing that actually this is a reference to the fact that gods (and some demigods) weigh more than men — ships groan under the weight of Heracles and Dionysus. So Menelaus, who has a puffed-up sense of his own grandeur, is concerned that the combined weight of his magnificent self and his half-divine wife will be too much for the ship to carry. This theory is insane. Please forget that I mentioned it. I just wanted to give an example of how weird tragedy scholars are.

In spite of those outliers, most scholars believe that it is a joke, and it’s “weirdly out-of-tune” because Menelaus is an extremely unimpressive character with no capacity to read a room, self-reflect, or say no to his hot wife. In other words, this bad fat joke does some work to tell you something about Menelaus as a character. What it does not do, presumably, is make the audience guffaw uproariously. It’s hard to imagine any director trying to play this line for actual laughs, since it’s an unfunny joke nested within a deeply harrowing play.

At least, that’s my take. Not everybody agrees. Edith Hall — again, an eminent tragedy scholar, and a wonderful proponent of Classics education in the UK — wrote on her blog just a few years ago, in a review of Anne Carson’s Trojan Women: A Comic:

Another characteristic of Euripidean tragedy is sudden lurching between agony and absurdist humour. The best joke in his oeuvre occurs in this very play, when Hekabe, fearing that Menelaus will be seduced by Helen into sparing her life, begs him not to sail back to Greece with the legendary beauty on the same ship. ‘Why?’, he asks in the Greek, ‘has she put on weight?’ The image of a now-obese sex kitten threatening to sink one of Menelaus’ Spartan triremes, occurring at a moment of utter despair, is a quintessentially Euripidean use of humour to throw pain into relief.

With respect to Professor Hall, whose work I really admire: yikes. Let’s leave aside the problematic use of the word “obese”1 — the claim here is that “has she put on weight?” is “the best joke in his oeuvre”? An oeuvre that includes Cyclops, a genuinely hilarious play? Really?

I’m not sure there’s any possible way to make this joke even slightly amusing. Part of me does wish that Emily Wilson, the translator who hurt so many sad internet misogynists’ fee-fees by translating Odysseus’ epithet polytropos at Odyssey 1.1 as “complicated,” had gone for a bigger swing than she did with “Has she put on too much weight?” Something that still makes him seem gross and unsympathetic and dumb in a Barstool Sports way, maybe. “Don’t worry, I’ll bring a seatbelt extender for her.” You know, that sort of thing. Still not actually funny, except to the kinds of gross hetero men who think women’s bodies exist only for their delectation or, failing that, their mockery.

I’ve been trying to do the hard work of unlearning my investment in diet culture. If you’re interested in that journey, there are so many great resources just on Substack alone, starting maybe with the amazing Virginia Sole-Smith and working with her backlog of interviews.

More recently, I really enjoyed philosopher

’s latest book, Unshrinking: How to Face Fatphobia. Manne also has a great newsletter!I’m a Manne fan/stan generally, and I cite Down Girl and Entitled all the time. Unshrinking was more memoir-heavy, which was different from her previous works in a way that really worked for me.

What Manne adds to the other great books I’ve read about fat liberation is the philosophical lens she brings to all of her work. One argument she makes, very convincingly, is that there is absolutely no moral imperative to lose weight — but there is a moral imperative against pressuring other people to do so. Simply put, the evidence suggests that trying to lose weight often does not work, and the correlation between losing weight and better health has been overstated. In fact, attempts to lose weight often lead to weight cycling, which has been proven to be unhealthy, and fatphobic stigma is also strongly correlated with worse health. Attempts to lose weight are unpleasant, unhealthy, and don’t work. There is therefore no moral reason whatsoever to prioritize weight loss for yourself or anyone else. I find this a beautiful and freeing thought.

In her conclusion, Manne raises the concept of body reflexivity, the idea that everyone’s body exists only for themselves. She writes:

Body reflexivity prescribes a radical reevaluation of whom we exist in the world for, as bodies: ourselves, and no one else. We are not responsible for pleasing others.

A natural corollary: your reaction to my body is not my problem—or the point, or salvation. The body is not an object for correction or colonization or consumption. I am sorry, not sorry, if my body leaves you cold, or you find it to be wanting.

My feeling about this can be best described as 😍😍😍. I just love it so much!

Manne critiques body positivity on the grounds that sometimes we may not feel very positive about our bodies, and that’s just fine. How I feel about my body is my business. It doesn’t exist for you. It exists for me.

That brings me back, finally, to Helen, whose beauty and body so rarely get to be *for her.* She’s the face (or breasts) that launched a thousand ships. She’s a prize to be won, or passed around, because of how beautiful she is. She very possibly has the least body reflexivity of anyone in Greek myth.2

You can even see hints of her sadness about that in Euripides’ works. In his Helen, performed just a few years after Trojan Women, Helen sings a song wishing she could rub her face out like a painting and replace it with an uglier one (Helen 262-3). Helen of Troy: potential body reflexivity role model. You read it here first.

The brilliant Aubrey Gordon calls the terms “overweight” and “obese” “reductive and judgmental by their very definitions” in her book “You Just Need to Lose Weight”: And 19 Other Myths About Fat People and writes, “The term ‘obese’ is derived from the Latin obesus, meaning ‘having eaten oneself fat,’ inherently blaming fat people for our bodies. A growing number of fat activists consider the term to be a slur, and many avoid it altogether.”

Or maybe Heracles has even less? Discuss!

This is like the grown-up version of my most recent piece (anti-fatness in the Percy Jackson books)--so specific and randomly similar. This was GREAT. 🙌🏼🙌🏼🙌🏼